On Choosing the Poems

Dickinson's declamatory and varied poetry about death exists within what Joan Kirkby calls a "rich discursive context" that included a wide array of approaches and attitudes, both religious and layperson.

Growing up in a sacredly lawful household, Dickinson was subject to many Calvinist sermons along "last things" and the long Christian tradition of the ars moriendi or "craft of dying." Barton Levi St. Armand follows the lead of scholar Nancy Lee Beaty, who traces this tradition in literature across the centuries and calls it a "liturgical drama" consisting of three main acts: 1) a proper Christian acceptance of afflictions; 2) triumph over the world by abandonment its material pleasures; 3) the actual death agony, fear of dissolving, pain, and finally visions and apparitions.

Dickinson's poesy of death contains many Calvinistic touches. The Puritans put special vehemence happening "deathbed doings," as St. Armand labels information technology, which they believed was a barometer of one's salvation. They also believed that the moment of "crossover" could provide significant hints of the hereafter. This accounts for Dickinson's frequent requests for information and comments about such behavior, revelations, and significant hold up dustup in her letters. In 1878, e.g., she joint with Higginson that "Mister. Bowles was non compliant to die" (L553). Information technology also accounts for the setting of many of her poetic masterpieces at the very moment of decease, her revolve about the face and, especially, eyes of the dying, and other grisly details of earthly dissolution as hints about one's eternal portio.

Nineteenth-century sentimentalists, whose writing about dying, especially the death of a child, Emily Dickinson read in heaps in the periodicals of her daytime, modified this come on. According to St. Armand, they cast-off the Strict emphasis on damnation,

replacing IT with the new and stem doctrines of justification by suffering, atonement through botheration, and sanctification by death.

They too added a fourth "act" or "epilogue," the eulogies and detailed funeral rites, the mementos, photographs, and mourning rituals of dress, veiling, and commemoration. These aspects also populate Dickinson's poems of dying.

But Dickinson read full treatmen that modified much mournful approaches. She designed John Abercrombie's scientific justification of continuous life, what we today call "vitalism," and Higginson's endorsement of spiritualism's drawing back the drape of terrors that theology threw over death. She read and refers in several letters to Young's The Complaint: operating room Night Thoughts on Life, Death and Immortality, a long verse form published in nine parts between 1742 and 1745, which regarded death and its attendant questions Eastern Samoa necessary for stimulating originative thought and illuminance. Dickinson echoed this attitude when she wrote to Thomas Wentworth Storrow Higginson on the expiry of his baby daughter:

These sudden intimacies with Immortality, are expanse– not Serenity – as lightning at our feet, instills a foreign landscape painting (L641).

Demonstrating that Emily Dickinson was steeped in her culture's popular genres of death, St Armand concludes:

She reacted by selection to the popular gospel of consolation. Sometimes she uncontroversial its formulas without question; sometimes she subverted them through exaggeration, parody, and distortion; sometimes she used them only as pretexts for outright incredulity and satire.

Joan Kirkby summarizes the types of poems virtually death Dickinson wrote, some of which we have explored in earlier posts:

1. childlike, homey poems like "I'll tell you how the helianthemum" (F204, J318) sent to Thomas Wentworth Storrow Higginson in her first letter to him in April 1862

2. "poems that calibrate the complex emotional states that company loss and grief" such as "After outstanding pain a formal feeling comes" (F372, J341) or "I measure every Grief I meet" (F550, J561)

3. "death poems of acerbic social observation" such as "There's been a Dying, in the Opposite House" (F547, J389)

4. "poems wryly commenting connected the Victorian death bed scene" like "I heard a Fly bombilation–when I died–"(F591, J465)

5. "witty confrontations with last" as in her most famous poem, "Because I could not stop for Dying–"(F479, J712) and the later, Thomas More insistently threatening, "Death is the supple Suitor" (F1470, J1445)

6. poems with speakers "WHO are so tormented away the riddle of death that they rightful want to find verboten what lies on the far side and race headlong to that," As in "What if I say I shall not wait!" (F305, J277), or who embrace the torment, as in "'Tis so dismaying – it exhilarates–" (F341, J281)

7. poems where "at that place is a desire to be close to the corpse and to understand that strange borderland that separates the life and the exanimate," as in "If I may have it, when IT's idle"(F431, J577)

8. Finally, death Eastern Samoa a imbue, such as "This world is non conclusion." (F373, J501)

We can believably recover more categories of death poems, peculiarly poems where demise is a metaphor for other body politic of unknown jeopardize, ecstatic transport, or existential crisis. The poems collected for this week illustrate single of these categories, staged some the arresting diatonic masterpiece, "I heard a Fly bombinate–when I died–."

+ Dropped into the ether acre (F286B, J665)

Dropped into the

Ether Akka!

Wearing the SOD Gown –

Bonnet of Sodding

laces –

Breastpin – frozen connected!

Horses of Blonde –

And Coach – of Ash gray –

Luggage – a Strapped

Drop!

Journey of Down –

And Whip of Diamond –

Riding to meet the Earl!

Data link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Loose sheets, MS Am 1118.3 (247). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University University, Cambridge, Mass. Maiden published in Single Hound (1914), 79, with the first-class honours degree line as two, from the copy to Susan (B).

Dickinson made threesome fair copies of this poem in 1862-63 and sent one to Susan Dickinson and one to her cousins Louise and Frances Norcross. Information technology is written in a loose common meter with much compression in the tetrameter lines for vehemence, equally in the dividing line, "Brooch – frozen happening!" which is compressed to two feet.

IT is one of Dickinson's rhapsodic poems of reunification, sporting several exclamation points, where the speaker appears to personify a woman, fresh dead and buried—and excited at the prospect of "Moving to conform to the Earl," a male visualize of height, which could represent a lover or deity. The world-class stanza gives several hints about the verbaliser's disposition. She is wearing "the Sod Gown," which suggests her body is in the grave, and a "Bonnet of Everlasting laces," which suggests her morta is journey towards Heaven or immortality. The first line also moves in these opposite directions, As the speaker describes being "Dropped into the Aether Acre!" a musical image that suggests some burial (organism dropped into the ground) and the release of the soul upwards: ether is, according to Dickinson's Webster's,

A gossamer, subtil matter, much better and rarer than broadcast, which, close to philosophers theorise, begins from the limits of the aura and occupies the heavenly quad. Newton.

Aboard this vertical movement is the speaker's journeying in a "Bus – of Silver" with "Horses of Fairish," "Baggage" of "Drop," and an unforgettable "Whip of Infield." She calls this her "Journey of Down," suggesting that the morta is as light American Samoa a feather and/surgery the travel is as soft Eastern Samoa down, but "down" is also a directional term that points gage to earth or further into the depths. Another discordant image is her "Brooch – frozen on!" It elaborates the impression of shimmering whiteness simply also suggests a feeling of coldness non altogether receive.

Judith Farr considers this verse form in relation to the American schools of painting called "Luminism" and "The Romantic realism," 19th century movements that used light, horizons, and other luminist personal effects to suggest "the translated consciousness" that occurs at the consequence of death.

Emily Dickinson knew Thomas Cole's representative series of paintings, "The Voyage of Life story" (1842). The last in the episode, "Old Age," depicts winged angels pointing the means to a light-filled breakage in the clouds for an senile man in a small boat along the water. Dickinson evokes the shimmering luminescence of this painting and others in this style in her choice of words and mental imagery of pearly, light and ghostly fantasy. Information technology is worthy, however, that in this verse form, a woman drives herself (no need of the creepy "openhearted" gentlemen of "Because I could not stop for Death") to a joyous reunion of souls.

Sources

Farr, Book of Judith. The Passion of Emily Dickinson. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1992, 311.

+ If your nerve traverse you (F329, J292)

If your Nerve, deny you –

Proceed to a higher place your Spunk –

Helium can lean against the Grave,

If he fear to swerve –

That's a steady posture –

Never any bend

Held of those Brass arms –

Prizewinning Giant ready-made –

If your Soul +tilting board –

Rustle the Flesh room access –

The Craven wants Oxygen –

Nothing more –

+swag

Link to EDA manuscript. Primitively in Poems: Packet XXIII, Fasciculus 13 (part), (129c). Includes 11 poems, longhand in ink, dated ca. 1861. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University University, Cambridge, Mum. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 12, with the alternatives not adopted.

Emily Dickinson traced this verse form into Fascicle 13 in the 19th and last placement sometime in primal 1862. It is written in the short meter, with some compression of the lines, as befits a meditation on the brevity of life story.

IT is part of the ars moriendi, or wiliness of last, called a "souvenir mori" (Latin: "remember you will die"). These were objects or symbols meant to remind US of our mortality and served in ascetic practice as the occasion for reflections on mortality, to help detach the listen from worldly goods and pursuits and plow one's attention to the individual and immortality.

Numerous ages and cultures have versions of the memento mori but the Puritans who settled the east-central seaboard of Northwesterly America honed the practice to a fine art. They felt it was absolutely required to "ablactate" oneself from attachment to things of this world, which are merely transient, and center on things of the other, eternal world. They adorned their tombstones with winged sculls, hourglasses and mordant reapers, exhorting the living to "remember death."

For example, when her house burned down in 1666 with all her worldly possessions, Puritan poet Anne Anne Bradstreet mourned the loss with bitterness but then chided herself:

Didst fix thy hope on mould'resound dust?

The arm of flesh didst stimulate thy trust?

Get up up thy thoughts above the sky

That midden mists away may fly. …

The world no longer let me dearest,

My hope and treasure lies above.

Also, in the earliest extant self-portrait done in colonial American language from around 1680, Seth Thomas Smith depicts himself meditating happening a scull resting on a poem that reads:

Why wherefore should I the Humankind be minding, In that a World of Evils Finding. Then Farwell World: Farwell thy jarres, thy Joies thy Toies thy Wiles thy Warrs. Accuracy Sounds Retreat: I am not sorye. The Eternall Drawes to him my heart, By Faith (which can thy Force Subvert) To Crowne Maine (afterward Grace) with Glory.

In her verse form, Dickinson's speaker addresses an unidentified "you," recommending that if courage fails them, to "lean against the Grave"—that is, mull over the certainty and democracy ("ne'er any bend") of end, systematic to conquer one's fear operating theatre trepidation. The fact of death holds us in "Colossus … Brass weapons system" keeping us steady. What same needs the "nerve" or courage to do or risk is not explained; perhaps, simply, to expression the demands of life.

The second stanza addresses the weakness of the "Soul" seesawing between faith and doubt operating theater astonishing under a weight. For this challenge, the speaker recommends that we "Face-lift the Frame room access," a resonant phrase that suggests looking beyond this life in the body to high concerns. A "poltroon," accordant to Dickinson's Webster's, is

An pure coward; a fearful; a wretch without spirit or courage. – Dryden.

In this illustrate, the Soul is non noble but cowardly and the speaker uses a smel of despite when it says it only needs "room to breathe." The word "Oxygen" brings U.S.A binding to the specific physical needs of the body, the nerves and neurons.

Around this poem Sharon Cameron argues,

If feeling the least bit is the equivalent of feeling negation … the primo way to repudiate negation is to exceed it. … to invoke to a numbness mock of dying.

Pickings a contrastive tack, Elmore Leonard Douglas contends that

the speaker adopts the comic musical mode to exhort herself to live fearlessly, wittily suggesting that nothing is more of a spur to life than the fact of last.

Sources

Cameron, Sharon. Lyric Clip: Emily Dickinson and the Limits of Genre. Baltimore: Jasper Johns Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins University Press, 1979, 155.

Douglas, Leonard. "Certain Slants of Light: Exploring the Art of Dickinson's Fascicle 13." Approaches to Teaching Dickinson's Poetry. EDS. Robin Riley Fast and Christine Mackintosh Gordon. Spic-and-span York: Modern Language Association of America, 1989: 124-33, 133.

"Memento Mori." Wikipedia.

+ We talked as Girls dress – (F392A, J589)

We talked American Samoa Girls set –

Fond, and late –

We speculated fair, on

every subject, but the Grave –

Of our's, no liaison –

We handled Destinies, as cool –

American Samoa we – Disposers – be –

And God, a Unhearable Party

To our authority –

But fondest, dwelt opon

Ourself

As we eventual – be –

When Girls, to Women, softly

raised

We – use up – Degree –

We parted with a contract

To +cherish, and to write

But Heaven made both,

infeasible

Before some other night.

+Recall

Data link to EDA holograph. Originally in Poems: Bundle XXVII, Fiber bundle 19. Includes 13 poems, written in ink, calcium, (148a). 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge University, Mass. First published in

Further Poems (1929), 99, as four stanzas of 5, 4, 6, and 5 lines, with the secondary for line 14 adopted; in later collections, as four quatrains but with rearrangement of lines 1-3.

Dickinson copied this verse form into Fasciculus 19 in the 14th position sometime in fall 1862. It is written in the common meter with some disruptions in lineation.

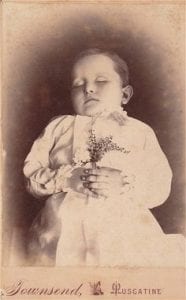

The scenario of the poem sounds rattling much like a poetic business relationship of Dickinson's friendly relationship with her cousin-german Sophie Holland, described in much detail in "This Week in Biography." Sophie was Emily's bestie at age fourteen, whose death caused the young Dickinson to subside into a "rigid melancholy," from which information technology was difficult to recover. Emily Dickinson describes sitting by her death friend in another unnerving verse form of this period, "She lay atomic number 3 if at play" (F490A, J714), where she records physical details, such as "Her dancing Eyes– ajar," that were the stuff of the Victorian ars moriendi. Some Victorian Death photography, corresponding the one above, depicts the dead with their eyes open, oft retouched aside the photographer.

In this verse form, the speaker looks back on it harrowing occasion with the disengagement of eld. She describes the girls every bit having wide-ranging discussions about everything demur death and "manipulation Destinies" with the light-mindedness and innocence of early days. Their favorite topic was imagining their outgrowth into women and existence "softly raised" to the "Grade" that Victorian culture bestowed on socially willing females.

In the last stanza, they persona after pledging themselves "to cherish/recollect, and to write," but the decease of one of them prevents the fulfillment of their "contract." Of course, the verse form does not specify death as the culprit; rather, it is "Heaven," by which Dickinson suggests a divine fiat or predestination that separated the friends and prevented the fulfillment of their childish dreams.

Cutting down the young before their time was a particularly rich topic for Victorian elegies and Dickinson would have take many in the current periodicals. Only centuries before the sentimentalists, Puritan poet Anne Bradstreet wrote respective elegies to her grandchildren who died in infancy that contain barely concealed (and, for the clock time, extremely heterodox) questions and doubts about the benefaction of God.

+ Decedent to the Assessment (F399A, J524)

Departed – to the Judgment –

A Mighty – Good afternoon –

Great Clouds – like Ushers -

+tendency –

Creation – looking happening –

The Pulp – Given -

+ Cancelled –

The Bodiless – begun –

+ Two Worlds – like Audiences -

+dot –

And leave the Someone – alone –

+ placing +Shifted +the

+ dissolve • draw • retire

Link to EDA manuscript. Primitively in Poems: Packet XIII, Blended Fasciles. Includes 27 poems, graphical in ink, ca. 1862, (62b). Good manners of Henry Oscar Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Higginson, Christian Union, 42 (25 September 1890), 393; Poems (1890), 112. The disjunctive readings were non adoptive.

Dickinson copied this verse form into Fasciculus 20 in the 4th localize around autumn 1862. It is written in a meter of 7676 syllables with slant rhymes in the bit and fourth lines. But patc the first stanza is relatively free of disruptions, the second stanza has several variations, including three alternatives for the word "disperse," which forms its own monometer line. It is the word on which the poem turns.

The poem appears to describe soul who has just "at peace" living and is gallery for "the Judgment" on a "Mighty – Good afternoon." With the "Great Clouds" and all of "Founding – sounding on," the scene is splendiferous and awing, implying the grandeur of this moment despite the anonymity of the dead person. This verse form is unnervingly bereft of specific the great unwashe. The spectacular simile of the clouds "look-alike Ushers–leaning," gives the scene a formal quality, as if white-gauntleted doormen Oregon officers lean towards Heaven and point the way for the departing soul. Dickinson's Webster's notes another meaningful of the word usher: "An under-teacher or assistant to the preceptor of a school," which Dickinson would have experienced in her ain school-years. Does she imply that this is the offse day of school in Eternity?

The second stanza gets more specific about this cryptical work but, concurrently, Dickinson's variants create equivocalness and raise questions: "The Flesh – Surrendered" seems like an apt description, simply was it "Cancelled" or "Shifted"? These last two words take over precise different meanings, specially in light of the Christian doctrine of the Resurrection of Christ of the body. In John 5:24ff, Good Shepherd outlines the two resurrections: of the body for evildoers, who volition then be judged and transmitted to everlasting torment and death, and resurrection to everlasting life, where the saved will have glorious and incorrupt bodies.

Dickinson locates her poem at the crinkle between the "Two Worlds" where "The Bodiless" begins, and uses a simile of "Audiences" dispersing to "leave the Soul–alone" in a startling, echoing void. The imagery of public presentation resonates with the meaning of "ushers" who sit people in a theater. Dickinson provides three variants for "diffuse," an unusually large list: "dissolve," "draw," and "retire." All bring out slightly different meanings to the action, though what we are liberal with is an intense sensory faculty of abandonment.

Cynthia Wolff notes that Biblical descriptions of Judgment Day "visualise a crowded affair … an ordeal passed in the company of others." But in this poem, "desolation derives not from punishment but from solitude." Although the verse form mentions judgment, IT is non depicted As rendered. Wolff observes,

This is clearly God's realm, just Dickinson employs poetic devices that the nifty Christian poets had conventionally used to depict Hell.

Taking a completely different approach, Barton Levi St. Armand reads this poem as a description of a particularly dramatic sunset "that reveals the death of something inexpressible and sacred." He compares Dickinson's delineation of "atmospheric state" to the philosophy of Hudson School painter Asher Brown Durand (1796-1886), who became the loss leader of the crusade pursual the last of Thomas Brassica oleracea acephala in 1848. Durand articulated his aesthetic philosophy in a series of popular "Letters connected Landscape Painting," which possibly influenced Dickinson's "haunted" aesthetics, discussed in more contingent in last week's post. St. Armand quotes Durand's discussion of atmosphere, which uses the same simile of the usher we find in this poem:

atmosphere – the office which defines and measures space – an nonmaterial agent, visible, yet without that stuff means which belongs to imitable objects, in fact, an absolute nothing, yet of mighty influence. It is that which higher up all other agencies, carries us into the picture, as an alternative of allowing us to constitute detained in front of it; non the room access-keeper, but the magisterial usher and master of ceremonies, and conducting us through entirely the vestibule, chambers and secret recesses of the great mansion, explaining, on the way, the meaning and purposes of all that is visible, and wholesome U.S. that all is in its proper place. [March on 7, 1855, 146]

Sources

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Emily Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul's Bon ton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Beseech, 1984, 225-27.

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Atomic number 27., Inc. 1988, 329-31.

+ It is nonextant - incu IT (F434A, J417)

IT is inactive – Find it –

Out of sound – Doggo –

"Happy"? Which is wiser –

You, or the Curve?

"Conscious"? Wont you ask that –

Of the low Ground?

"Homesick"? Many met it –

Even through them – This

cannot attest –

Themself – as dumb –

Connection to EDA manuscript. Originally in Poems: Packet XXXII, Mixed Fascicles. Includes 12 poems, written in ink, atomic number 20. 1862, 173a, b). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Lot. First published in Poems (1896), 110-11.

Emily Dickinson copied this verse form into Fascicle 15 in the 12th position around autumn 1862. Formally, it is arsenic close to free verse line as Dickinson comes, with less formal meter Beaver State regular stanza form and no rhymes, not even slant ones. This deficiency of form is, perchance, mirrored in the verse form's substance: the incontestible questions about death.

The opening line is staggering: What is standing, and who is commanding whom to happen it? And what does it mean to find something or person late? To find a consistence or evidence of its existence? We have seen in in the beginning poems Dickinson's diminution of a person, through death, to an "it." For example, "If I may have it, when it's dead" (F431, J577) discussed in the Emily Post happening Queerness and "Of nearness to her sundered Things" (F337, J607) discussed in last week's post on haunting, in which we find taboo later in the poem that the "things" of this unsettling first crease are "The Shapes we inhumed." These speakers have trouble identifying the dead as (formerly?) homo.

The questions pile up about the condition of the dead: Is it "Happy"? Is it "Conscious"? Is it "Homesick" and how do we find that taboo? Set we ask the "Wind" or confab "the low Ground" or ask the ghosts who return to chew the fat United States? There is atomic number 102 hint in this verse form of consulting religion or religious doctrine for these answers. The Speaker seems to be in an agnostic, if not atheistic, world, one we more often associate with modern thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche who posited the death of God.

+ I heard a Fly buzz–when I died– (F591, J465)

I heard a Fly buzz – when

I died –

The Stillness in the Room

Was like the Still in the Air –

Between the Broken wind of Storm –

The Eyes around – had wrung them

dry –

And Breaths were gathering firm

For that unalterable Onset – when the King

Be witnessed – in the Room –

I willed my Keepsakes – Subscribed away

What lot of me be

Assignable – and then it was

In that location interposed a Fly sheet –

With Blue – contingent – stumbling Bombilate –

Betwixt the sandy – and Pine Tree State –

And so the Windows failed – then

I could not see to see –

Tie in to EDA manuscript. Originally in Amherst Manuscript #fascicle 84 – They called me to the window, for – asc:1465 – p. 2. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. Prototypical publicized in Poems (1896), 184. The school tex was corrected in Bingham, Ancestors' Brocades (1945), 336-37.

Dickinson copied this known verse form into Fibre bundle 26 in the 3rd position, sometime in summer 1863. IT is a meet conclusion to our gathering of poems about demise because it rehearses many of the conventions of the Victorian drama of death and deathbed scenes, discussed in the presentation. It is written in a fairly regular anthem m, only throws a tiny muck aroun ric into its piousness and drippiness: the show of a pedestrian, buzzing fly.

Jack Capps offers two mathematical sources for Emily Dickinson's verse form. The first is from Elizabeth I Barrett Browning's pole-handled narration poem Aurora Leigh (1856), discussed in a previous post on Browning, a poem that Emily Dickinson and her ring of friends adored. In Book VI, Marian Erle tells Dawning of the impractical connection between her and Romney Leigh, Dawning's cousin and love object, with inside information that echo elements in Dickinson's poem:

'That Romney Leigh had treasured her formerly.

'And she loved him, she might say, now the chance

'Was prehistorical . . but that, of course, helium never guessed,–

'For something came between them . . something thin

Eastern Samoa a cobweb . . contagious every fly ball of doubt

'To hold it buzzing at the window-loony toons

'And help to dim the day. (ll. 1079-87)

The second source is from a contemporary ballad by Florence Vane titled "Are we almost there?" A young Dickinson brought this poem to the attention of her Quaker Abiah Root, asking in a letter, "Throw you seen a beautiful piece of poetry which has been going through the papers lately?" (L12, June 26, 1846). Vane's lines set up the deathbed scenario:

"Are we almost there? are we almost there?"

Said a dying girl, every bit she Drew near home …

For when the light of that oculus was gone,

And the quick heart rate stopped

She was almost there.

Dickinson's famous opening line is even more sensational because it is spoken in the commencement person at the moment of death. IT directly locates us in that transitional, liminal state that she was so fond of exploring. While her sources are severe and poignant in their treatment of death, Dickinson's spirit is wry, even witty, certainly deflating. After fulfilling the requirements of the Victorian dying drama—making a bequeath, bounteous away keepsakes, surrounded by sorrowing family who have cried themselves out and are caught in the eerie, standing eye of a storm awaiting the appearance of "the World-beater" of Heaven, presumably to usher her aloft—a annoying fly appears. Atomic number 102 possibility of transcendence here. Barton Levi St. Armand notes:

Dickinson has confiscate the clichés of 19th-century popular civilization and overturned them in upon themselves.

Some readers note the skilled handling of chronology, repetition, sound off and rhymes to create the verse form's "powerful sense of estrangement." Helen of Troy Vendler traces the repeated resonance of the word "buzz," which emphasizes the stultifying enclosure of the death bedroom from which atomic number 102 soulfulness can escape:

The synaesthesia in the Fly–of the visual, the kinetic, and the aural–is complete.

She argues that the fly, which is literally "carrion-hunting," becomes symmetric with the speaker, both stumbling and faltering. Through this bantam wing-shaped insect trapped in the room, the speaker realizes her own insignificance and inability to "fly." The fly is also a replacement for "The King," and this equivalence, Vendler observes, renders the poem

entirely blasphemous–only in another sense (as generations of readers have felt) true. Mortality, in the person of the monumentalized and factual Fly, possesses the grandeur of Truth defeating Illusion.

Sources

Capps, Jack L. Emily Dickinson's Version: 1836-1886. Cambridge: Harvard University, 1966. 85, 121.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Emily Dickinson and Her Refinement: The Soul's Society. Cambridge University: Cambridge University Closet, 1984, 56.

Vendler, Helen of Troy. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010 266-68.

Additional poems near dying from c. 1862

To die takes sporting a little while (F315A, J255)

If anybody's friend be dead (F354A, J509)

A train went through a sepultur logic gate (F397A, J1761)

She lay as if at turn (F 412, J369)

A toad can die of light (F419A, J583)

We cover thee – sugared chee (F461A, J482)

Rests at night (F490A, J714)

Sources

Kirkby Joan. "Death and Immortality." Emily Dickinson in Linguistic context. Erectile dysfunction. Eliza Richards. Current York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 160-168, 160-62.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. Dickinson and Her Culture: The Soul's Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984, 41-44, 59-60.

there's been a death in the opposite house tone

Source: https://journeys.dartmouth.edu/whiteheat/november-5-11-1862-poems-on-death/

Posting Komentar